Carl Mautz: Antique Photo Collector and Publisher

Interview by Casey Walker

in Wild Duck Review,

Sept/Oct 1996, Nevada City, CA

Carl Mautz: Antique Photo Collector and Publisher |

|

I began life in Portland, Oregon, in 1943. Education through public schools resulted in a law degree

from the University of Oregon in 1969. I married my college sweetheart and had two beautiful

children. A spiritual curiosity surfaced in 1973 and the yearning lead me to the Fellowship of

Friends, a Gurdjieff-Ouspensky group, in 1975. I moved to the Fellowship's property in Yuba

County two years later. While there, I served several years as the attorney for the Fellowship. In

1984 I opened an office in the mountain town of Brownsville where I practiced what I call "country

law" for a wonderful community of folks. In 1993 I began a period of transition which led to

disassociation from the Fellowship, retirement from the active practice of law, selling my home

and moving to Nevada City in February, 1995. Since 1971, my avocation has been collecting and

dealing 19th century photographs. I am currently developing a small publishing company

specializing in subjects pertinent to history as reflected in photography as art and artifact, although

a pure poetry book is beckoning which will contain some design elements borrowed from historic

photography.

Casey Walker: Would you begin by describing how and why you began collecting photographs?

Carl Mautz: When I graduated from law school, I took an independent route as a solo attorney,

meaning I started from scratch, had no money and ample dead time. Being active by nature, I

began to collect things, and most of the things I collected had visual aspects such as graphic or

photographic imagery. My law practice evolved and supported my wife and children, but collecting

was my heart's refuge. I was a lawyer by default, following the path of my father and brother.

Collecting was a gift from my mother - an artist, artisan, collector and designer rolled into one. After

experimenting with different collections, I found that photographs called to me. They were

unappreciated, as boxes of them were commonly dumped. I began collecting at garage and estate

sales. Soon I was studying their history. Eventually, I became expert at recognizing aspects and

features of photographic images that were ignored by all but the more astute collectors and

curators.

CW: What was the catalyst for collecting photographs as opposed to other things.

CM: When my father died in 1969 and my grandmother went into a nursing home a few years

later, I inherited piles of old photographs. My father had been a locally famous football player in

Oregon, and there were many sports photographs. I loved seeing my Dad in his 1916 uniform,

before they wore pads and face masks - the old look. The photographic image allows intimate

access to a different time. Would you like to time travel? Just grok an interesting old photograph,

and feel the space depicted. Do you want to experience an older culture as evidenced by old

portraits and snapshots? Look deeply into the scene and let your emotions connect with the faces,

the dress, the grooming, the implements and so forth. When the collecting passion arose in me, I

dove in, buying whatever I could find. I first read Photography and the American Scene: A Social

History, 1839-1889 by Robert Taft written in the 1938. It was a watershed book that triggered my

understanding of what I was looking at and lead me to other key books such as Beaumont

Newhall's History of Photography. Eventually, I'd read enough to know what I was doing, and I

understood the art in photography as well as the artifact. Photography is so new. Compared to

other art forms it is still a youth, but even so, its history is rich with an ebb and flow of styles and

formats, goosed by incessant technological incursions and spiced by human inspiration.

| Cabinet card portrait by A. A. Montano, Honolulu, Hawaii, c. 1880

|

CW: What are some of the categories photography falls into, and which do you prefer?

CM: Portraiture plain and simple has always intrigued me. Not from a technical standpoint so much

as from the human interface caused by looking at a person's portrait. So many things emerge from

the image: character, ethnicity, charm, psychology, style, place - any way you want to characterize

it. It is the human form and how that form is presented. Portraiture breaks down into sub-categories

such as occupationals (people with the tools of their trade), military, children with toys, post-

mortems, and so forth. Then there s genre photography, a category reflecting daily activity, such as

street life, fairs, picnics, weddings, etc. Closely related would be documentary photographs such as

that produced by the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression by photographers

such as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans and Russell Lee. Documentary images relate to a

particular theme such as migrant workers, ethnic groups, industrial practices, and the like. The list

of categories and subcategories goes on and on. News photography is related but somewhat

different in that such images capture moments relevant to a story of immediate interest.

CW: Do you have a specialty in photography that you collect?

CM: Sure, my affinity is the early calling card photographs, known everywhere in its time and today

to collectors as "carte-de-visite", or "cdv" for short. The period of popularity of this format was the

late 1850s to around 1880, so the historical periods reflected in this format include the Civil War,

American expansion throughout the West, including the Indian Wars, European colonialism and

exploration, industrial innovation and expansion, etc. I particularly enjoy California images, although

my scope is worldwide. I also appreciate the imagery of artistic photographers such as those

involved in the Photo Secession lead by Alfred Stieglitz. Something in my psychology, however, has

always prevented me from spending money on first level photographers. Unfortunately for my

heirs, this trait precluded purchasing, for as little as $50, prints by quality photographers like

Edward Weston which now commonly sell in five figures. I didn't get it it all seemed like fantasy to

me. But on the level that fantasy works to generate money, dollars keep clustering around the

finest works of master photographers.

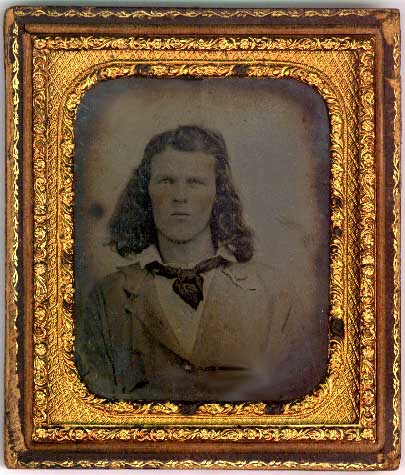

Sixth-plate ambrotype of a miner, photographer unknown, _______________________________________

|

|

CW: What is it about antique images that intrigues you?

CM: The photograph is an imprint of time transmitted by light and caught in matter. In the image is

a teaching about the transitory nature of all things, all people and of ourselves. If you gaze into

these photographs and let them stir your feelings, a familiarity begins to form around how

individuals assume their reality. Each person is shaped by his or her own history and context, and

each person makes myriad assumptions about what is real and what is true, but when you realize

that those assumptions are merely assumptions, then you know that you do the same thing. The

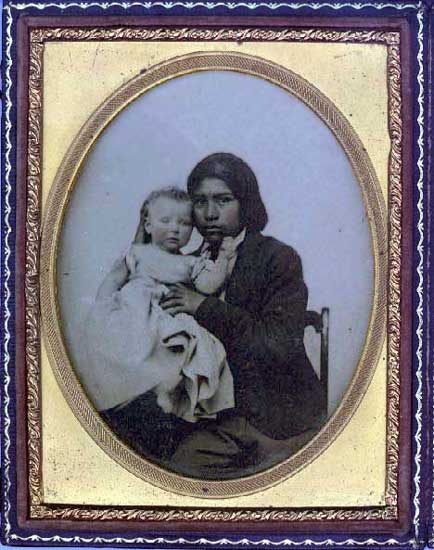

portrait of the Maidu youth, a servant likely stolen from his family to be "civilized", with the white

child who is his charge, implies many things about the meeting of different cultures - who

dominates, who serves, who has a future, whose past is legitimized, whose manners or mode of

dress is "correct", etc. Then focus on the emotional reality of these two individuals around the

moment when this reflection of light was fixed on the photographic plate. It was very difficult to take

a child's picture in the 1850s, because of the long exposure time. The child trusts the youth. The

child could be calm and still for a relatively long time in close proximity to him, and it appears that

the youth was comfortable with the child. In other words, affection flowed between them, despite

the context which brought them together which we now understand to be a brutal destruction of

culture and displacement of people, not to mention outright genocide occurring all around the

vicinity where this photograph was taken. But this Maidu youth was functional in his role as

caretaker of the child and probably felt hope in a future role within a world where his parents'

traditions were overwhelmed and invalidated by the new, dominant paradigm. Do you see how

much can be discerned from a photographic image?

|

Quarter-plate ambrotype by Robert Vance, probably from his Marysville studio, c. 1855, of a Maidu youth, possibly Raffle, servant of John Bidwell, Chico, California. |

CW: And how does this empathy translate to wisdom for ourselves?

CM: The Book of Ecclesiastes asserts that there is nothing new under the sun, and I think that's

true and evidenced in photography. Sure, there were no personal computers 25 years ago, but in

the sense of human behavior and drama, there is nothing new under the sun. You see this in the

faces of the women laced up in corsets and covered with incredibly intricate, overflowing petticoats,

gowns and accoutrements, or men with broad cravats, vests and great coats, all tightly wrapped to

keep nature at bay. You begin to see within this antique milieu the faces of your friends, the kids

you grew up with, your parents and their friends, fellow workers and so on, but in a different cultural

context with its own set of assumptions, its own sense of reality. But really, nothing has changed in

the psychology and consciousness of the individuals. The stories of the past are relevant to us,

because we live the same stories and can empathize with those whose experience parallels ours.

So while the photographs tell us of the outward differences of one age from another, in the faces

and figures we can see ourselves and that no set of assumptions is permanent. It seems ironic to

me and a poetic triumph that in less than a hundred years Euro-American culture doffed its clothes

in California and subscribes avidly to the more congenial minimalism of native dress. The climate

had its way with the humans.

CW: How are photographic images like poems?

CM: I'm not sure how tight to weave the analogy, but poetry creates imagery within, and

photography creates imagery without. Both seek an emotional response, and in the most artistic

examples, deeper understanding and greater awareness. As I've been saying, a meditation on a

photographic image can stimulate internal imagery which associates from the subject depicted, not

unlike the result of careful contemplation of a poem. Lately, in some of my own poetry, I've been

adding photocopies of images as design elements in the presentation of the poem. My poem

"Wonder of Birth, Death and The Circle" was among the first, and I made it into my Christmas card

in 1993, using the visual image of the beaded belt, which was the impetus for the poem.

| WONDER OF BIRTH, DEATH AND THE CIRCLE

Found a beaded belt the other day, in a shop near Markleeville, The receipt said beaded necklace, but it was a belt It was a jewel, I saw, as I held it in the mountain light, Do you know Indian beadwork? Do you? I don't, but My belt - my - well, it's only mine in trust, right? And there in a mountain canyon, lying among the junk, CM\11/16\93 |

CW: How has your collecting translated into publishing?

CM: I've been publishing books for a long time, although most were self published works of poetry

for friends or arty little photo essays using snapshots or prints from old negatives. I wrote a novel

about my first ten years in the Fellowship, The Autobiography of Henry Diver, which was a cathartic

exercise from the viewpoint of a believer who needed to reconcile the pervasive contradictions and

gnawing stagnation in a world that seemed utterly enchanting at an earlier stage. I self-published

the novel as well, distributing about twenty copies to friends. My commercial publishing began

many years ago with a small reference work for photography collectors entitled Checklist of

Western Photographers. This book lead to another reference work entitled Photographers: A

Sourcebook for Historical Research and the soon to be printed Biographies of Western

Photographers. But last year I published four books on historical photography and local history, one

of which boasts the earliest daguerreotype of Nevada City on its cover. The fun news is that in

addition to a number of other reference works for photography collectors and historians, I have two

books in the works which penetrate artistic realms. The first is the manifesto of an eccentric,

fascinating friend named Ken Appollo who has traveled the world hawking antique images for

twenty-five years. He's literally a legend among photography collectors, because he always lands

on your doorstep with astonishing images. As an Italian whose grandfather sold vegetables by the

roadside, he collected a brilliant array of images of organ grinders, street peddlers and town

eccentrics in his years of itinerant dealing. The name of this book is Humble Work & Mad

Wanderings: Street Life in the First Century of the Machine Age. It is essentially a picture book, with

Ken's compelling personal perspective complementing the images. The second book is a cycle of

poems called The Ancestors Are Calling Down the Rainbow by a talented poet named Arupa

Chiarini. As part of a personal analysis, she worked through her personality patterns resulting from

a severely dysfunctional childhood. Her technique was to meditate and call in the spirits of various

ancestors going back to a baby who died in 1624 in Massachusetts. After years of dialogue with the

muse, the voices of her ancestors told their stories and this cycle of poems emerged as catharsis, healing

and renewal. I'm very excited about publishing the cycle in book form and presenting it as a performance

piece as well.

CW: Are you planning to publish anything else as a personal expression of your interest in

photography?

CM: My heart is empathetic. It's easy for me to empathize, and this is something many people

seem to like and respond to, although some seem threatened by it as well. I feel a pull to share

what I see in images with others; that is, I want to share the feeling I elicit from photographs by

presenting the images through a creative, compelling medium, which for me means the art of the

book. One long term project I have in mind derives from an album I purchased last year which I

have no intention of ever selling. It was put together either by a Nez Perce family or by a missionary

working at the Lapwai Agency in Idaho around 1905. These are not the kind of photographs

collectors want, because these Indians are dressed like Euro-Americans, having acculturated to a

significant degree. But Euro-American dress and all, the imagery is powerful, because it tells the

story of a people in an oft-told and difficult transition - coping with a conquering, enemy tribe. The

cool thing is that these folks not only survived, but their traditions survived on a level that keeps the

clan viable as a cultural self. My aim will be to create from that album a book which will elicit

profound empathy for these folks through their own snapshot imagery.

CW: Do you have an interest in photographs of Native California people?

CM: Yes, and that has been a relatively recent interest which developed as a result of a close

friendship with a Maidu basket weaver and association with the California Indian Basket Weavers

Association. I found that few collectors knew or cared about the natives of this land. It seems the

native people were so well adapted to the environment that they could not conceive of a people

such as the Euro-Americans who would boldly stride in, take whatever they wanted and hunt them

as rabbits, maligning each and every aspect of their culture along the way. One result of this

gratuitous conquest was that California natives were denigrated as "diggers", and few took their

pictures, since they didn't fit the mold of the "noble savage" favored by romantics. The result is that

images of Native Californians were seldom made and thus are scarce and difficult to collect. There

is an excellent book by the Sierra Club entitled Almost Ancestors: The First Californians. I would, of

course, like to publish more on this subject, but so far I haven't found anything as coherent as the

Nez Perce album from which to portray the visual poetry imperative to a book which is also a work

of art.